Sample Chapter

All words, phrases or sentences taken from Annie’s letters are italicised.

Prologue

c/o Mr Burnett

No 1 Kings Cross Rd.

W.C.

My dear wife

My reason for not writing to you is that I did not think you would care to hear from me.

For sixty years the letter had died its own kind of lingering death, decomposing and curling in the darkness, developing that dingy tan that only comes from decay. Yet as I fished it out from the surrounding rubbish I could see that it was stained by deeper things; soiled by human longing; a weary patina of rented rooms, yellowing wallpaper, drawn curtains and loneliness.

‘Why do you never write?’

My reason for not writing to you is that I did not think you would care to hear from me.

He squeezed her. ‘Would it be asking too much’, he hissed from behind the tight-lipped firmness of that first sentence, ‘for you to try and control yourself and keep your voice down, so that we might at least conduct this conversation in private?’

As to my reasons for leaving you as I did I think we had better leave that to be discussed at some future time.

A file somewhere was closing. He was moving on.

I am very pleased to hear that you are getting well and strong & sincerely trust that you will soon be your old self again.

The tension began to ease as he stepped clear. Her illness had been a terrible bore but she was evidently on the mend and he might cast her off. He talked of a job in London and began edging towards the needful, the point in every letter when he tickled her for money and clothes.

Now if you really wish the past to be of the past, and feel disposed to assist me to get what is absolutely necessary to take a position that will be worth £2 a week to me, I will endeavour to be all that you may wish in the future.

The same old promises.

Should you feel disposed to assist me in this case (in spite of what has happened) it will be for a mutual benefit, and as soon as I am settled I will look for a suitable place for you to come to – in the meantime will consider what is best to be done re. furniture etc.

That final transformation: his petty cadging turning itself into a business proposition. Should you feel disposed to assist me in this case was nothing less than a rare opportunity, her final chance to back a winner.

Should you fail me in this case I shall go out East with no intention whatever of returning

I am

Your husband

Gus Bowen

Chapter 1: Attic

‘I think you’d better come and look at this.’

We were lifting carpets and staring at the bruised face of floorboards.

‘Dry rot?’ I asked, prodding away at the timber and scratching my head.

‘I think you’d better come and look at this.’

The voice again, this time louder and echoing down from the attic. I climbed the stairs and tried to prepare myself. He was standing beside a door leading into the roof eaves where a fierce December wind was slicing through the slates and making the little door seem anxious and agitated. I inched closer, he stretched out his hand, gave me a metal torch, and then smiled, ‘See for yourself,’ he said.

I knelt down, he held the door steady, and I fumbled with the torch. Finally, I forced myself into the darkness.

I had grown up with this house. It had been there in the corner of my eye when I ran to school and had imprinted itself on my childhood memory, so when I opened my first box of crayons and was asked to draw a house, I drew a doll’s house with a door at the centre, a window either side, three windows above, and two wisps of smoke rising up in the languid air. And above it, the sky. Always the blue sky. For what is a Georgian house if not a doll’s house? It was there when I came back from college in the early 1970s and took a job as a postman.

The House

I walked up the drive, a clutch of letters in my hand, the early morning sun shimmering through the beech trees. At the side of the house, a door was wide open and I stared into a cool whitewashed passage running to the back where a second door gave views of the garden beyond. Splashes of red and yellow. Edna called it her ‘tulip time’. And that was the moment I fell in love. Another twenty years and we were sinking everything we had after Jim and Edna decided to sell.

It seemed as though the two of them had spent a happy retirement camped out in the garden. There were photographs to prove it. Before we took possession of the house, I think it’s safe to say that the photographs took possession of us. Jim and Edna dug out their family album and we gazed longingly at the images; strings of onions hanging glossy and plump in the old washhouse; Jim in a white collarless shirt glimpsed through the branches of an apple tree, mowing the lawn on a summer afternoon; Edna wrapped in a white sheet, doing an impish impression of a Greek statue. And every time we talked of buying and selling, they walked us into the garden. Nothing else was needed. The garden did its work.

We met Jim and Edna on the last day as they loaded up their belongings.

‘Don’t forget’, Jim said as he ran his fingers through his hair and looked over our heads to the house, ‘you’re just stewards. One day you’ll hand it on.’ Part of me loved him for that, but then as the removal van veered round the corner, the house sank into a glum silence, like an abandoned dog, and I began to have doubts.

I flicked on the torch and crawled into the darkness. As the wind blew through the roof slates, I could feel the attic door fretting against me. The last golden eagle to fly across an English sky and think it could get away with it was shot down in the summer of 1917. Or so they say. I’m not entirely convinced. I think the old bird somehow dodged the shot and struggled north, taking refuge in our roof. How else could I explain it? Here, in the crumpled darkness between the partition wall and the chattering slates, it must have nursed its wounds and lived in brutal squalor. The size of the nest was unbelievable; straw and feathers scattered everywhere and mixed in amongst the carnage, mummified birds in different states of decomposition. Caught in the torch beam, the scene was monstrous. I moved the light from side to side, trying to find something reassuring, but all I could see was death and decay. Everything covered in an uncanny dust, silky in texture and strangely scented – part soot, part cobwebs, part something else.

‘All of it,’ he said, pointing to the darkness, ‘all of it needs clearing before our lads start tomorrow.’ The firm was scheduled to start treatment of the woodwork the next morning. ‘Shouldn’t take more than an hour.’

Overalls, thick balaclavas, plastic goggles, wet handkerchiefs, pink rubber gloves – we put on anything that might protect us. Finally, we took a deep breath and crawled into that little hole of ungodliness. No room for shovels or spades or anything like that, so everything had to be lifted by hand. Dead birds, broken glass, rotting paper, stained cloth, all feeling strangely alive through the rubber gloves. Handful by handful, we lifted the debris and pushed it through the door where it lay in heaps, waiting to be bagged. And all the while, we kept tightening the handkerchiefs across our faces, thinking they would protect us, but they never did. There was no protection from this. We finished after midnight and dumped the bags into an unloved corner of the garage.

The soft ticking of time.

Sunlight in the garden, daffodils blooming, the old hawthorn hedge growing fat and green. Somehow or other we had weathered the first winter, the winter that nearly broke us; the winter when the house fell vacant and looked bruised. Everything needed to be damp-proofed, so the interior plaster on the ground floor had to be hammered away to a height of three feet. Whenever we drove home on those winter nights and stepped through the door, the place looked forlorn. We gritted our teeth. Now that the walls were ruined, we may as well set about rewiring the place, and whilst we were at it, a new central heating system seemed a sensible option. So floorboards came out and holes gaped and the house sagged.

But somehow it never quite fell. We had come through. The central heating was working, the house warm, Nat King Cole was playing on the radio, sunlight was streaming through the windows, the world seemed to be blossoming again. Standing in a makeshift bedroom on that Spring morning, looking out through dusty glass, I saw the air swelling with leaves.

‘I wonder what’s in those bags?’

‘What bags?’ Gill asked.

‘In the garage. The ones from the attic.’

‘I thought you threw them out?’

I stared blankly at the trees. Why had the bags come back to haunt me on this Spring morning?

Gill climbed out of bed and looked at her husband. ‘Have some breakfast first.’

‘Just a quick look.’

Once inside the garage, I grabbed the nearest bag and dragged it into the sunshine. Sharp slivers of glass were cutting through its sides and spewing out the contents. Circling the heap, I began lifting torn flaps and squinting inside. Everything as I remembered it: an ugly mix of crumpled paper and stained cloth, broken glass and crockery, and every time I poked a finger into the squalor, I seemed to find a dead bird, its soiled feathers matted to the bone. So in truth, I don’t know what drew me to the edge.

I reached down and fished it out. A Victorian photograph. A quick wipe across my sleeve and two ghosts appeared. The first stood before me in a three-quarter coat with a light waistcoat and watch chain hung across his belly. A bearded man, balding and probably in his forties, wearing light-coloured trousers with a stripe down the sides, and radiating a faint air of male menace. One arm was bent against a thickening waist and he presented himself to the world as a man who was not to be trifled with. The woman sat on a chair, wrapped in her own melancholy. A dark air of resignation enveloped her. I noticed how her jet-black hair was parted down the middle and brushed back with a glossy kind of severity.

The soft ticking of time. In the filth and squalor, dust and droppings, I had found something, and it was only then that I remembered what I had seen on that grim December night, but not seen at all; poignant faces staring out at me from mid-Victorian photographs; fat envelopes ripe with words; cheap Edwardian postcards covered in pencilled messages; neatly-folded newspaper cuttings . . . handbills . . . concert programmes . . .

When I came to my senses, there were faces everywhere, rising up from every level of the rubbish, all beseeching me. I spent the morning saving them, pulling them out like survivors, lining them up in neat rows on a hastily-improvised dustsheet draped across the lawn. And there I sat in the midst of this new kingdom like an astonished god. And when there were no more photographs to pluck, I went deeper, and then I found it.

It was filthy and crumpled, almost unreadable and pockmarked with dead insects; a grubby inconsequential piece of paper that would change my life. I held it against the soft afternoon light and saw for the first time that it was a letter. Brushing aside the last of the cobwebs and flicking off the dead insects, I started to read. Dear Mrs. Bowen, Your kind grateful letter received last evening too late to answer. The normal pleasantries about health and weather were dropped like coats to the floor and the writer rushed to the point, grabbing her reader by the shoulders. Well dear friend I note all you said about Mr. Bowen and that vile woman.

I steadied myself. I am truly surprised at Mr. Bowen lowering himself in such a manner and making so little of his lawful wife . . . More dirt had to be brushed away before the next bit could be read . . . but there are some women that would tempt the best men born with their fascinating ways . . .Two wood pigeons sat in the bay tree above my head cooing like lovers. . . . but you may depend, he will tire of her before long, the vile drunken hag.

And so it started; the unplanned journey. Soon, there were more letters and more still. Incredibly, so much had survived. Like the tiny envelope I came across a few days later addressed to:

Miss Annie Johnson

North Road

Gainford

Near Darlington

England

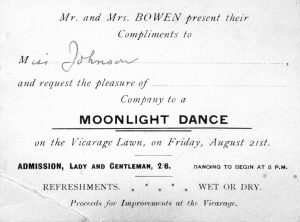

I blew off the dust and the envelope fell open. Inside there was an invitation:

Invitation

The way it fell open said everything. It had been read a thousand times, and then a thousand times more; a fading memento of an August night; the little envelope that she probably opened every day of her life, lifting it carefully from her box of souvenirs.

A week later, the phone rang. The secretary of the Family History Society wanted to know if I would give them a talk. I had done several over the years, so whilst I started casting round for a new idea, I told him about my find. Perhaps his members would be interested in this hoard of old photos and letters? He was sure they would.

Six months later, I regretted it. I found myself sitting anxiously at my desk, devoid of inspiration. Three letters lay before me and I began shuffling them in a desultory sort of way, hoping for a miracle. There they lay: the invitation to the Moonlight Dance, the letter from Gus to his ‘dear wife’, and the scandalised talk of a ‘vile woman’.

The invitation had been sent to a woman called Annie Johnson who had obviously lived in our house. This much was certain. Died here by the look of it, for how else had her letters and all her other possessions ended in our attic? When the invitation was sent, she was living in Gainford, a small village more than forty miles away to the west.

The name ‘Bowen’ kept cropping up. It was there at the top of the invitation – Mr. and Mrs. Bowen present their compliments to Miss Johnson – and there in the letter addressed to Dear Mrs. Bowen. Then there was the breathless gossip of Mr. Bowen and that vile woman. Finally, I was staring at Gus’s signature – I am Your husband Gus Bowen.

Everything in pieces. Over the previous months, I had found seventeen letters from Gus. Some dated, some not. Reading them as Annie must have done, I came to know his voice, the way he cajoled her, the promises he held out of better times to come. I developed an ear for his style of lovemaking; those little declarations of love that flowed so effortlessly from his pen. Then there were the practical reasons why he couldn’t see her this coming weekend. Finally, the turning points in every letter when the sinuous flow of his male charm wriggled towards money. Some letters came from London, some from Lancashire, some from exotic locations in the Mediterranean. I caught glimpses of him in Constantinople, then in Bolton, then in South Africa, and Annie, for that matter, never stopped moving either. She flitted from one set of rented rooms to another, sometimes in York, sometimes in London, sometimes in villages dotted about the Cleveland countryside, always looking for that warmer place by the fire. In the midst of this never-ending restlessness, there was talk of ‘troubles’ and the occasional mention of a girl called ‘Beezie’. Gaps too, lots of them, so I knew from the start that I would be piecing together a broken jigsaw.

All of Gus’s letters were packed into a four-year period between 1898 and 1902, so the Moonlight Dance was almost certainly in the 1890s. I went back to the invitation. The date was there – Friday, August 21st at 8pm – but lacked a year. The only clue was a smudged postmark on the envelope that seemed to have a solitary six on its edge. Friday fell on August 21st only twice in the 1890s, once in 1891 and once in 1896, so it seemed I had my year.

‘They met in 1896 and parted in 1902,’ I said, and then laughed. Here I was tut-tutting like a disapproving vicar, ‘It’s all over before it starts.’

During those endless months of emptying bags, I found more than a hundred and thirty photographs, but only two in frames. The faces that Annie lifted from her albums and placed on her mantelpiece. One of them was a picture of an old gentleman in a tweed suit sitting before the camera, a walking stick resting gently between his legs. There was no name and I gazed at the face knowing that this was someone special, a man who Annie loved. The most obvious candidate was her father. The other frame had two catches on the back and I struggled to release them. The catches were stiff but finally came free. A wooden flap fell open and I saw for the first time that Annie had written a name.

I lifted the photograph and looked at Gus’s face.

‘So there you are.’